The Legend of John Henry Play Guide

What to know – before the show!

[bs_collapse id=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

[bs_citem title=”Play Synopsis” id=”citem_193a-4246″ parent=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

On the day John Henry was born, thunder rolled through the valley like a mighty steam locomotive. He was always big for a youngin’, as tall as his mama at four years old! John was already working with the steel hammer that would seal his fate with the C&O Railroad Company. He knew from the moment that hammer graced his hands he was destined to be a steel driving man.

As soon as the Civil War ends, he sets out to get a job driving steel for the C&O Railroad. He goes to the docks to see if he can find something that will take him up the Mississippi River.

In order to gain passage on her riverboat, Captain Greene challenges John Henry to a cotton rousting race against Will “I Am” Tippit. With his mighty strength, John Henry wins the race and gains passage aboard the Greene Line Steamer.

When the crew gets to Louisville, they arrive in the middle of a terrible storm with a loose rudder. John fixes it in a jiffy and the crew is able to safely dock the boat. He soon learns he has one day to get up to Cincinnati before C&O heads out. Luckily for John Henry, a man named Oliver Lewis with a horse called Aristides rides by and challenges John Henry to a race. If John wins, he gets to borrow the horse. Sure enough, John Henry beats the man fair and square, and he and Aristides ride all the way up to Cincinnati, ensuring he makes it in time.

When he arrives in the big city, he turns his ear toward the ringing sound of steel pounding against steel. He finds the C&O Railroad and their captain, Thomas McDaniel! The captain swiftly sends John Henry out to work on the railroad, driving spikes with his new partner, Polly Ann. They know it is fate that brings them together, and the two quickly fall in love.

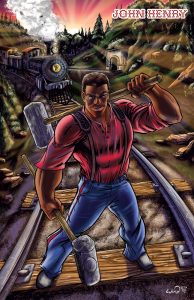

John and Polly join the crew heading out east to continue building the railroad to Talcott, West Virginia. The only thing stopping them: a huge mountain. Can’t go over, can’t go under, so they build the Big Bend Tunnel straight through it. John and his crew set to slowly drilling through the mountain of solid rock. Reinforcements soon arrive in the form of a steam drilling machine that threatens to put the crew out of work.

John Henry challenges the machine to a race in hopes of saving their jobs. He barrels through the mountain and beats the machine, but John Henry collapses from exhaustion and dies the way he was born, with a hammer in his hand.

[/bs_citem]

[bs_citem title=”Play Before the Play” id=”citem_5ae1-0fed” parent=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

CREATE YOUR OWN FOLKTALE

The Legend of John Henry is based on a real steel-driver, but the story itself has been changed as it has been passed down over time. For instance, while contests were common, there is no evidence of a contest between a man and a steam drill.

Have each of your students create their own folktale about someone they know. Have them begin by gathering facts about their chosen person then extend the facts into a larger than life context. Click on the link below and print the folktale writing guide to help your students create their story.

[bs_button size=”md” type=”primary” value=”Folktale Writing Guide” href=”https://www.lctonstage.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Folktale-Writing-Guide.pdf”]

Have each student write a one or two page tale based on their newly created hero/heroine. Finally, have them draw a picture from their story or design a statue commemorating their character.

KAS: RL.3.2, RL.3.3, C.4.3, C.5.3

TRAVEL BY RAILROAD

Have students make maps of the railroads that crossed the U.S. in the 1800s. Mark the important stops along the way, as well as which lines were used more commonly for passenger travel and which were used for freight. What significance did the trains have for people living at that time? Have students accompany their maps with a first-person account of traveling between two cities by train. What was the station like? Did they (as a passenger) eat or sleep on the train? How much luggage could he or she bring? What did he or she do to pass the time? What sort of scenery could be seen out the window? How fast was the train? Have students share their accounts with the class.

KAS: 5.G.HE.1, 5.G.MM.1, 5.E.IC.1 4.G.KGE.1

AROUND THE BEND

Click the link below and print the Around the Bend activity for each of your students so they can learn about various folktales across the country.

[bs_button size=”md” type=”primary” value=”Around the Bend Activity” href=”https://www.lctonstage.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Around-the-Bend-Activity.pdf”]

KAS: 5.G.HI.2; 3.H.CO.1; 3.G.GR.1

[/bs_citem]

[bs_citem title=”Contextual Article” id=”citem_0f09-1977″ parent=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

JOHN HENRY: TRACING THE LEGEND

John Henry’s competition with the steam drill at Big Bend Tunnel near Talcott, West Virginia has been preserved in song, or more specifically a ballad. However, variations in each version of the ballad have raised the question of who John Henry really was or if he existed at all.

The earliest versions of John Henry were not always accurate. The steel-driving hero was often confused with John Hardy, a Black outlaw who was hung on January 19, 1894 after killing a man in a gambling dispute in a Shawnee coal camp. The confusion between John Henry and John Hardy was deeper than the similarity of their names. In a 1916 letter, W.A. MacCorkle, former governor of West Virginia, mixed up the two men by writing that John Henry, the famous steel driver of the 1870’s, had later gone wrong and killed a man in the 1890’s.

The historical record was finally set straight in the late 1920’s by Louis Chappell, a West Virginia University professor. Chappell showed beyond doubt that John Hardy was a small, tough man who was still in his twenties at the time of his hanging, making it impossible for him to have been a steel driver more than twenty years earlier at Big Bend Tunnel.

The bigger question became where was this Big Bend Tunnel mentioned in so many versions of the John Henry song and was there really such a place at all? Variations of John Henry were collected all over the country with a localized version coming from even further away in Jamaica. The legend was adapted into a stage play as well as a 1950 children’s book—John Henry and His Hammer—written by Harold Feltonhad.

Guy B. Johnson, a University of North Carolina sociologist, published the first book on the subject in 1929, John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend. He searched for Big Bend Tunnel and John Henry lore all over the southern and western United States. For a time, he thought he’d found the roots of the story in Alabama. It seems that in 1887, work was under way to put railroad tunnels through Oak Mountain and Coosa Mountain, about fifteen miles east of Birmingham. Guy Johnson looked into this theory throughout the 1920s, but he gave up on it because he couldn’t tie down the facts.

To get his leads, Johnson advertised in local newspapers for John Henry stories. One of his key correspondents C. C. Spencer, but Spencer’s memories were so confused that he mixed up John Henry with John Brown, the abolitionist who led the 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry. Eventually, Johnson followed up on a tip that John Henry originated in southern West Virginia in the 1870’s.

The main seam was finally mined when Louis W. Chappell of West Virginia University published John Henry: A Folk-Lore Study in 1933. Chappell had been delving into John Henry’s legend for years and was angry that Guy Johnson’s book had been published first, and with much less pertinent material. Chappell had extensive knowledge of what happened in Summers County in the early 1870’s. He knew a tunnel had been built through Big Bend Mountain near Talcott, and since he did his legwork in the 1920’s, he was able to find people who’d been around during construction. Some of Chappell’s sources claimed to have actually seen John Henry wielding his hammer, though their memories were often fuzzy.

Historians have now found their way to Talcott which is only about 100 miles from the Logan County home of the Williamson Brothers & Curry, the first West Virginians to record the ballad of John Henry in April 1927. We can only wonder, did the Williamson Brothers learn John Henry from the first generation of the song’s performers, not far from where it was written? [/bs_citem]

How to grow – after the show!

[bs_citem title=”Extend the Experience” id=”citem_a8e0-0382″ parent=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

THE GREATEST BALLAD EVER SUNG

In The Legend of John Henry, the characters sing a song or ballad that tells the story. Ballads have traditionally been passed down orally from generation to generation. They are akin to poems that provide narration in short stanzas. Have students write a poem or short ballad about a character in a story they have read (e.g. – a fairy tale or a book they’ve had to read for class) or choose someone they know who has done something brave or awe-inspiring (e.g. – a parent, friend, or celebrity). Encourage students to include a variety of details about their character such as what they look like, what their personality is like, and their accomplishments. If students are struggling with choosing a tune for their ballad, encourage them to rewrite the words to a popular song such as “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” or “Old McDonald.”

Once your students have finished writing, have them perform their ballads for the class. For added fun, type up each student’s ballad and print them in a collection of poems and ballads!

KAS: C.3.3; C.4.3; MU:Pr6.1.4.a

TALL TALE COLLAGE

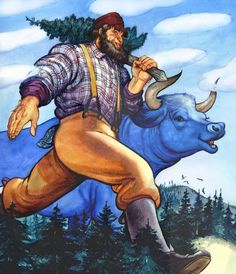

Begin by having students research a variety of famous tall tales such as:

- The Story of Johnny Appleseed

- Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox

- The Legend of Miss Sally Ann Thunder Ann Whirlwind

Then have students make a collage illustrating a tall tale of their choice. Each collage will be a collection of clues that other students use to try guessing the folktale. For example, a collage for The Legend of John Henry might include pictures of a hammer, a mountain, a racehorse, and train tracks.

Hang the collages around the room and see how many can guess which tall tale is which!

KAS: VA:Cr2.1.1; VA:Cn11.1.4; VA:Cr2.2.5

DRIVING FORCE

Several times in the play, John Henry found he was good at more things than just driving steel. Why didn’t he just stay on the riverboat and shovel coal? Why was it so important to John Henry to drive steel? Ask your students what goals they want to work toward. Do they think they can reach those goals right away or will they need to work for them by doing other things?

After your discussion, have your class write personal reflections pieces about their personal goals and what it is going to take for them to achieve them. Then ask your students to simplify their goal into a single sentence or phrase (e.g. Be a Good Friend! or Honor Roll, Here I Come!). Provide students with art supplies so they can create personal banners with their goal. Hang the banners around the room to inspire your class to reach their goals!

KAS: ES.P.5; ES.P.4; ES.I.4; ES.I.2

STEEL DRIVING TABLEAUX

Give students time to think about their favorite moments from LCT’s production of The Legend of John Henry. Then divide your class into groups of four or five and have each group choose three moments from the play to illustrate by making a frozen picture, or tableau. After each group has shown their three frozen images, have them choose one of the tableaus to turn into a short scene by adding movement and dialogue. Remember, students can act out things other than people in their images and scenes such as a steam drill or a horse.

KAS: TH:Re7.1.4; TH:Pr4.1.1.b; TH:Pr6.1.2

[/bs_citem]

[bs_citem title=”Suggested Reading” id=”citem_3165-23de” parent=”collapse_7c0c-a603″]

If you like tall tales from across America, you may also like…

American Tall Tales by Mary Pope Osborne

Meet America’s first folk heroes in these nine wildly exaggerated and downright funny stories together in one superb collection.

The Jack Tales: Folk Tales from the Southern Appalachians by Richard Chase

Everyone thinks they know the story of Jack and the Beanstalk. Join Jack on eighteen adventures from the mountains of North Carolina handed down through the generations.

The Tales of Uncle Remus by Julius Lester

Whether he’s besting Br’er Fox or sneaking into Mr. Man’s garden, Br’er Rabbit is always teaching a valuable lesson.

Her Stories: African America Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales by Virginia Hamilton

These stories focus on the magical lore and wondrous imaginings of African American women in a spirited celebration of strengths, dreams, and the precious gift of life and love from generation to generation.

[/bs_citem]

[/bs_collapse]

Educational materials sponsored by